Design Patterns - Introduction

A summary of GoF Design Patterns

Before I start talking about what are the design patterns I would like to dedicate a few words to this picture that you can see in the official cover of Design Pattern - Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software.

If you did not know who Maurits Cornelis Escher was, he was an one of the greatest artist of the twentieth century who made mathematically inspired woodcuts, lithographs, and mezzotints.

His work features mathematical objects and operations including impossible objects, explorations of infinity, reflection, symmetry, perspective, truncated and stellated polyhedra, hyperbolic geometry, and tessellations.

Joking, the description above is extremely consistent with the thought you have when you are a beginner to design patterns. I could talk for hours about what I think about this masterpiece but it is better to move on to the concrete, or rather to the abstract …

Contents

- What Is a Design Pattern?

- Describing Design Patterns

- The Catalog of Design Patterns

- Organizing the Catalog

- How Design Patterns Solve Design Problems

What is a Design Pattern?

Christofer Alexander says,

"Each pattern describes a problem which occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice" [AIS+77, page x]

Probably the best way to classify design patterns is to talk about their four main elements:

-

The Pattern name is simply the name that describe the pattern. Usually it is one or two word in relationship with their Solution and Consequences. Attributing a Pattern name we can use this to talk with our colleagues, write a documentation and many other thing without ambiguity.

-

The Problem describes when we apply the pattern. It might be a representation such as how to implements an algorithm or data structure as an Object.

-

The Solution describes the elements that we should use to implements the design pattern. These elements could be related to themselves and the collaboration and responsibilities are more important.

-

The Consequences are the result and trade-off that the design patter should returns.

Describing Design Pattern

Design Pattern - Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software book describe design patterns using a consistent format. Each pattern is divided into section according to the following template.

Pattern Name and Classification

A good name is vital, because it will become part of your design vocabulary. The pattern's classification reflects the scheme I introduce in section Organizing the Catalog.

Intent

Following question: What does the design pattern do? What is its rationale and intent? What particular design issue or problem does is address?

Also Known As

Other well-known names for the pattern, if any.

Motivation

A scenario that illustrate a design problem and how the class and object structures in the pattern solve the problem.

Applicability

What are the situations in which the design pattern can be applied? What are example of poor designs that the pattern can address? How can you recognize these situations?

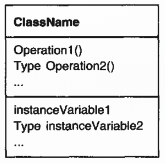

Structure

A graphical representation of the classes in the pattern using a notation based on the Object Modeling Technique (OMT) [RBP+91]. I also use interaction diagrams [JCJO92, Boo94] to illustrate sequences of request and collaborations between object.

Participants

The classes and / or objects participating in the design pattern and their responsibilities.

Collaborations

How the participants collaborate to carry out their responsibilities.

Consequences

How does the pattern support its objectives? Whar are trade-offs and results of using pattern?

Implementation

What pitfalls, hints, or techniques should you be aware of when implementing the pattern?

Sample Code

Code fragments that illustrate how you might implement the pattern in C++ or Smalltalk.

Known Uses

Example of the pattern found in real system.

Related Patterns

When design pattern are closely related to this one?

The Catalog of Design Patterns

-

Abstract Factory - Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes.

-

Adapter - Convert the interface of a class into another interface clients expect. Adapter lets classes work together that could not otherwise because of incompatible interfaces.

-

Bridge - Decouple an abstraction from its implementation so that the two can very independently.

-

Builder - Separate the construction of a complex object from its representation so that the same construction process can create different representations.

-

Chain of Responsibility - Avoid coupling the sender of a request to its receiver by giving more than one object a chance to handle the request. Chain the receiving object and pass the request along the chain until an object handles it.

-

Command - Encapsulate a request as an object, thereby letting you parameterize clients with different requests, queue or log requests, and support undo able operations.

-

Composite - Compose objects into tree structures to represent part-whole hierarchies. Composite lets clients treat individual objects and compositions of objects uniformly

-

Decorator - Attach additional responsibilities to an object dynamically. Decorators provide a flexible alternative to subclassing for extending functionality.

-

Facade - Provide a unified interface to a set of interfaces in a subsystem. Facade defines a higher-level interface that makes the subsystem easier to use.

-

Factory Method - Define an interface for creating an object, but let subclasses decide which class to instantiate. Factory Method lets a class defer instantiation to subclasses.

-

Flyweight - Use sharing to support large numbers of fine-grained objects efficiently.

-

Interpreter - Given a language, define a representation for its grammar along with an interpreter that uses the representation to interpret sentences in the language.

-

Iterator - Provide a way to access the elements of an aggregate object sequentially without exposing its underlying representation.

-

Mediator - Define an object that encapsulates how a set of objects interact. Mediator promotes loose coupling by keeping objects from referring to each other explicitly, and it lets you vary their interaction independently.

-

Memento - Without violating encapsulation, capture and externalize an object's internal state so that the object can be restored to this state later.

-

Observer - Define a one-to-many dependency between objects so that when one object changes state, all its dependents are notified and updated automatically.

-

Prototype - Specify the kinds of objects to create using a prototypical instance, and create new objects by copying this prototype.

-

Proxy - Provide a surrogate or placeholder for another object to control access to it.

-

Singleton - Ensure a class only has one instance, and provide a global point of access to it.

-

State - Allow an object to alter its behavior when its internal state changes. The object will appear to change its class.

-

Strategy - Define a family of algorithms, encapsulate each one, and make them interchangeable. Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it.

-

Template Method - Define the skeleton of an algorithm in an operation, deferring some steps to subclasses. Template Method lets subclasses redefine certain steps of an algorithm without changing the algorithm's structure.

-

Visitor - Represent an operation to be performed on the elements of an object structure. Visitor lets you define a new operation without changing the classes of the elements on which it operates.

Organizing the Catalog

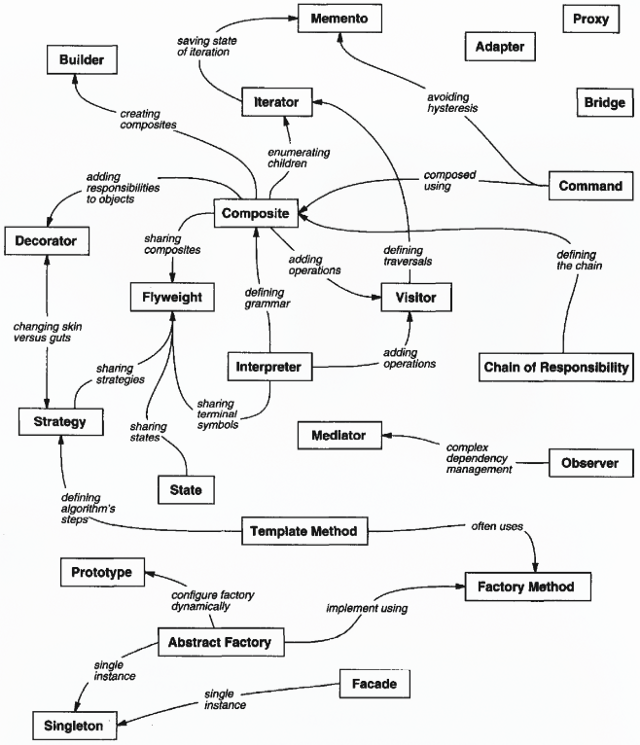

Design pattern vary in their granularity and level of abstraction. The classification helps you to learn the patterns in the catalog faster.

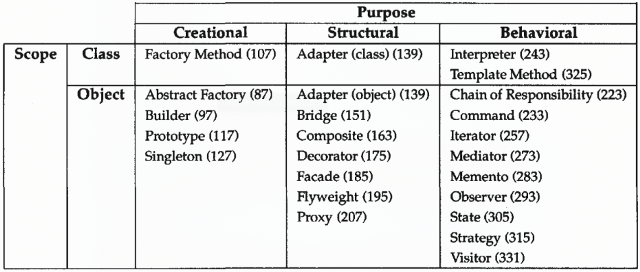

The book classify design pattern by two criteria (Table 1.1). The first criterion, called purpose reflects what a pattern does. Patterns can have either creational, structural, or behavioral purpose. Creational patterns concern the process of object creation. Structural patterns deal with the composition of classes or object. Behavioral patterns characterize the ways in which classes or objects interact and distribute responsibility.

The second criterion, called scope, specifies whether the pattern applies primarily to classes or to objects. Class patterns deal with relationship between classes and their subclasses. Object patterns deal with object relationship, which can be changed at run-time and are more dynamic.

How Design Patterns Solve Design Problems

Finding Appropriate Objects

Object-oriented programming are made up of objects. An object packages both data and the procedures that operate on that data. The procedures are typically called methods or operations. An object performs an operation when it receives a request from a client.

The hard part of object-oriented design is decomposing a system into objects because there are many factor come into play: encapsulation, granularity, dependency, flexibility, performance, evolution, reusability, and on and on.

Object oriented design methodologies favor many different approaches. You can write a problem statement and create classes and operations. Or you can focus on the collaboration in your system. Or you can model the real world and translate objects found during analysis into design.

Design patters help you identify less-obvious abstractions and the objects that can capture them. For example, objects that represent a process or algorithm don't occur in nature. The strategy pattern describes how to implement interchangeable families of algorithms. The state pattern represent each state of an entity as an object.

Determining Object Granularity

Object can vary in size and number. They can represent everything down to the hardware or all the way up to entire software.

Design patterns address this issue as well. The facade pattern describes how to represent complete subsystem as object and the flyweight pattern describe how to support huge numbers of object at the finest granularity

Specifying Object Interfaces

Every operation declared by an object specifies the operation's name, the objects it takes as parameters, and the operation's return value. This is known as the operation's signature. The set of all signatures defined by an object's operations is called the interface to the object.

A type is a name used to denote a particular interface. We speak of an object as having the type "Window" if it accepts all requests for the operations defined in the interface named "Window." Two objects of the same type need only share parts of their interfaces. Interfaces can contain other interfaces as subsets. We say that a type is a subtype of another if its interface contains the interface of its supertype.

When a request is sent to an object, the particular operation that's performed depends on both the request and the receiving object. The run-time association of a request to an object and one of its operations is known as dynamic binding.

Moreover, dynamic binding lets you substitute objects that have identical interfaces for each other at run-time. This substitutability is known as polymorphism, and it's a key concept in object-oriented systems.

Design patterns help you define interfaces by identifying their key elements and the kinds of data that get sent across an interface.

For example, the Memento pattern it describes how to encapsulate and save the internal state of an object so that the object can be restored to that state later.

Specifying Object Implementations

An object's implementation is defined by its class.

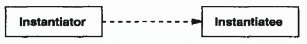

Objects are created by instantiating a class. The object is said to be an instance of the class. The process of instantiating a class allocates storage for the object's internal data (made up of instance variables) and associates the operations with these data.

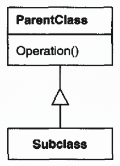

New classes can be defined in terms of existing classes using class inheritance. When a subclass inherits from a parent class, it includes the definitions of all the data and operations that the parent class defines.

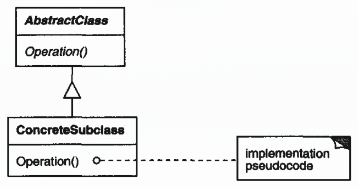

An abstract class is one whose main purpose is to define a common interface for its subclasses. An abstract class will defer some or all of its implementation to operations defined in subclasses; hence an abstract class cannot be instantiated. A concrete class may override an operation defined by its parent class. Overriding gives subclasses a chance to handle requests instead of their parent classes.

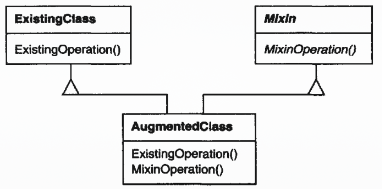

A mixin class is a class that's intended to provide an optional interface or functionality to other classes. It's similar to an abstract class in that it's not intended to be instantiated. Mixin classes require multiple inheritance:

Class versus Interface Inheritance

It's important to understand the difference between an object's class and its type.

An object's class defines how the object is implemented. The class defines the object's internal state and the implementation of its operations. In contrast, an object's type only refers to its interface – the set of requests to which it can respond. An object can have many types, and objects of different classes can have the same type.

It's also important to understand the difference between class inheritance and interface inheritance (or subtyping). Class inheritance defines an object's implementation in terms of another object's implementation. In short, it's a mechanism for code and representation sharing. In contrast, interface inheritance (or subtyping) describes when an object can be used in place of another.

Many of the design patterns depend on this distinction. For example, in the Composite pattern, Component defines a common interface, but Composite often defines a common implementation. Observer, State, and Strategy are often implemented with abstract classes.

Putting Reuse Mechanisms to Work

Inheritance versus Composition

The two most common techniques for reusing functionality in object-oriented systems are class inheritance and object composition. As I've explained, class inheritance lets you define the implementation of one class in terms of another's. Reuse by subclassing is often referred to as white-box reuse.

Object composition is an alternative to class inheritance. Here, new functionality is obtained by assembling or composing objects to get more complex functionality. Object composition requires that the objects being composed have well-defined interfaces. This style of reuse is called black-box reuse, because no internal details of objects are visible.

Inheritance and composition each have their advantages and disadvantages. Class inheritance is defined statically at compile-time. It also make it easier to modify the implementation being reused. But you can't change the implementations inherit from parent classes at run-time, because inheritance is defined at compile-time. The implementation of a subclass becomes so bound up with the implementation of its parent class that any change in the parent's implementation will force the subclass to change.

Object composition is defined dynamically at run-time through objects acquiring references to other objects. Composition requires objects to respect each others' interfaces. Objects are accessed solely through their interfaces, we don't break encapsulation. Any object can be replaced at run-time by another as long as it has the same type.

Favoring object composition over class inheritance helps you keep each class encapsulated and focused on one task. Your classes and class hierarchies will remain small. On the other hand, a design based on object composition will have more objects.

Delegation

Delegation is a way of making composition as powerful for reuse as inheritance [Lie86, JZ91]. In delegation, two objects are involved in handling a request: a receiving object delegates operations to its delegate.

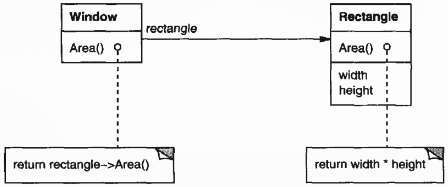

Differs from inheritance because it is no longer accessed via this or self. For example, instead of making class Window a subclass of Rectangle, the Window class might reuse the behavior of Rectangle by keeping a Rectangle instance variable and delegating Rectangle-specific behavior to it.

The main advantage of delegation is that it make it easy to compose behaviors at run-time and to change the way they are composed. If we want, our window can become a circular at run-time, assuming Rectangle and Circle have the same type.

Delegation has a disadvantage it shares with other techniques that make software more flexible through object composition: Dynamic, highly parameterized software is harder to understand than more static software.

Several design pattern use delegation. The State, Strategy, and Visitor patterns depend on it.

Inheritance versus Parameterized Types

Another (not strictly object-oriented) technique for reusing functionality is through parameterized types, also known as generics and templates. This technique lets you define a type without specifying all the other types it uses.

Parameterized types give us a third way (in addition to class inheritance and object composition) to compose behavior in object-oriented systems. Many designs can be implemented using any of these three techniques.

There are important differences between these techniques. Object composition lets you change the behavior being composed atrun-time, but it also requires indirection and can be less efficient. Inheritance lets you provide default implementations for operations and lets subclasses override them. Parameterized typeslet you change the types that a class can use. But neither inheritance nor parameterized types can change at run-time.

Relating Run-Time and Compile-Time Structures

Consider the distinction between object aggregation and acquaintance and how differently they manifest themselves at compile- and run-times. Aggregation implies that one object owns or is responsible for another object. Generally we speak of an object having or being part of another object.

Acquaintance implies that an object merely knows of another object. Sometimes acquaintance is called "association" or the "using" relationship. Acquainted objects may request operations of each other, but they aren't responsible for each other.

In this diagrams, a plain arrowhead line denotes acquaintance. An arrowhead line with a diamond at its base denotes aggregation:

Designing for Change

The key to maximizing reuse lies in anticipating new requirements and changes to existing requirements, and in designing your systems so that they can evolve accordingly.

Design patterns help you avoid this by ensuring that a system can change in specific ways.

There are some common causes of redesign along with the design pattern(s) that address them:

-

Creating an object by specifying a class explicitly. Specifying a class name when you create an object commits you a particular implementation instead of a particular interface. Design pattern: Abstract Factory, Factory Method, Prototype.

-

Dependence on specific operations. When you specify a particular operation, you commit to one way of satisfying a request. By avoiding hard-coded request, you make it easier to change the way a request gets satisfied both at compiled-time and run-time. Design pattern: Chain of Responsibility, Command.

-

Algorithmic dependencies. Algorithms are often extended, optimized, and replaced during development and reuse. Object that depend on an algorithm will have to change when the algorithm changes. Therefore algorithms that are likely to change should be isolated. Design patterns: Builder, Iterator, Strategy, Template Method, Visitor.

-

Tight coupling Tight coupling leads to monolithic systems, where you can't change or remove a class without understanding and changing many other classes. The system becomes a dense mass that's hard to learn, port, and maintain. Design patterns use techniques such as abstract coupling and layering to promote loosely coupled systems. Design patterns: Abstract Factory, Bridge, Chain of Responsibility, Command, Facade, Mediator, Observer.

-

Extending functionality by subclassing Customizing an object by subclassing often isn't easy. Every new class has a fixed implementation overhead. Defining a subclass also requires an in-depth understanding of the parent class. Object composition in general and delegation in particular provide flexible alternatives to inheritance for combining behavior. New functionality can be added to an application by composing existing objects in new ways rather than by defining new subclasses of existing classes. Design patterns: Bridge, Chain of Responsibility, Composite, Decorator, Observer, Strategy.