Abstract Factory - Object Creational

By Dmitry Zhart (refactoring.guru)

Intent

Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete class.

Also Known As

Kit

Motivation

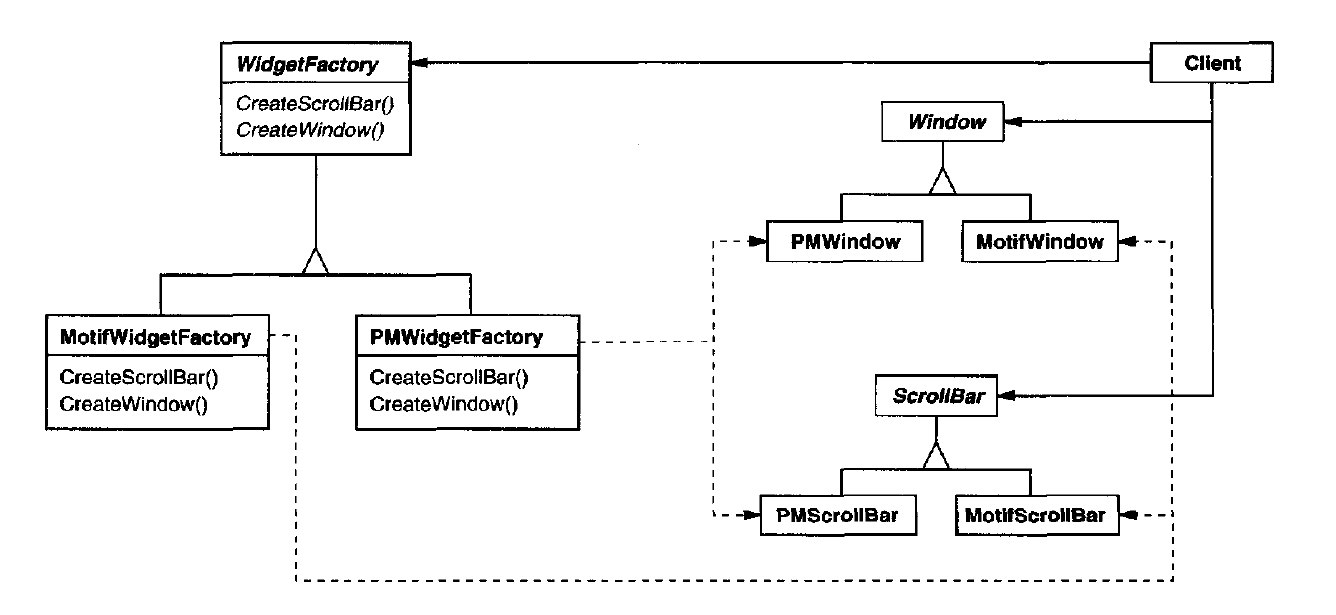

Consider a user interface toolkit that supports multiple look-and-feel standards. Different look-and-feel define different appearances and behaviors for user interface "widgets" like scroll vars, windows, and buttons. Instantiating look-and-feel-specific classes of widgets throughout the application makes it hard to change the look and feel later.

We can solve this problem by defining an abstract WidgetFactory class that declares an interface for creating each basic kind of widget. There is also an abstract class for each kind of widget, and concrete subclasses implement widgets for specific look-and-feel standards. WidgetFactory's interface has an operation that returns a new widget object for each abstract widget class. Clients call these operations to obtain widget instances.

There is a concrete subclass of WidgetFactory for each look-and-feel standard. Client create widgets solely through the WidgetFactory interface and have no knowledge of the classes that implement widget for a particular look and feel.

A WidgetFactory also enforces dependencies between the concrete widget classes. A Dummy scroll bar should be used with a Dummy button and a Dummy text editor, and that constraint is enforced automatically as a consequence of using a DummyWidgetFactory.

Applicability

Use the Abstract Factory pattern when

-

a system should be independent of how its product are created, composed, and represented.

-

a system should be configured with one of multiple families of products.

-

a family of related product objects is designed to be used together, and you need to enforce this constraint.

-

you want to provide a class library of products, and you want to reveal just their interfaces, not their implementations.

Structure

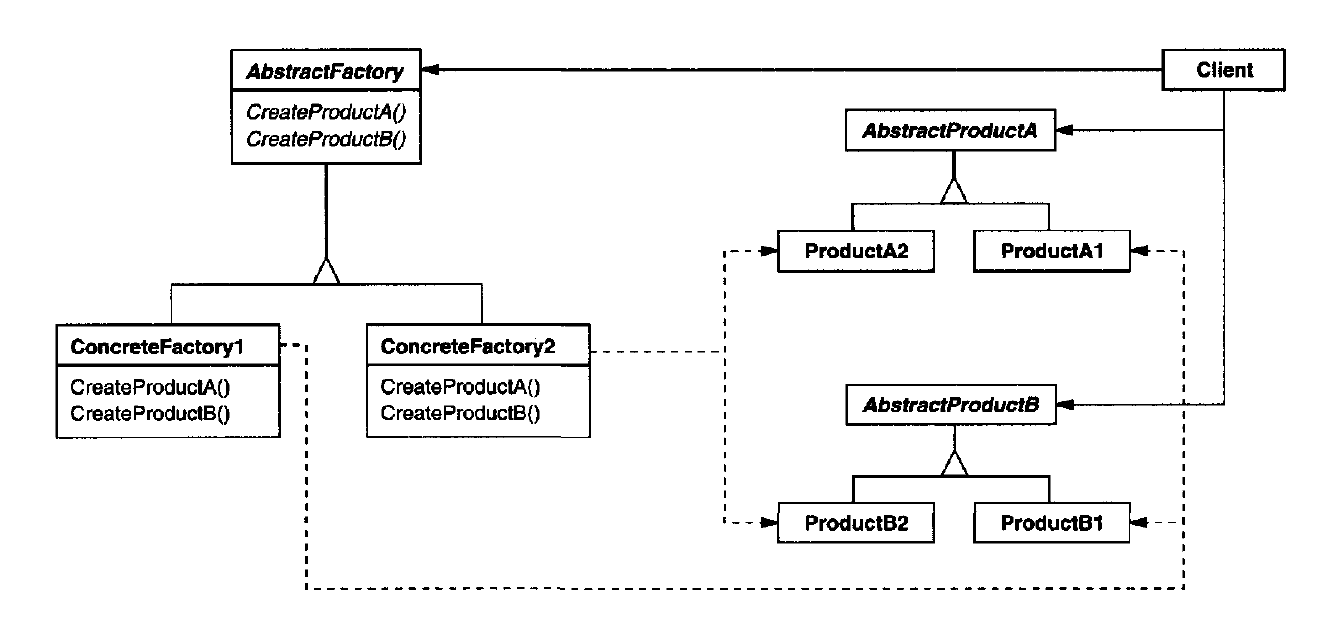

Participants

AbstractFactory

(WidgetFactory)

- declares an interface for operations that create abstract product objects.

ConcreteFactory

(DummyWidgetFactory, TWidgetFactory)

- implements the operations to create concrete product objects.

(Window, ScrollBar)

- declares an interface for a type of product object.

ConcreteProduct

(DummyWindow, DummyScrollBar)

-

defines a product object to be created by the corresponding concrete factory.

-

implements the AbstractProduct interface.

Client

- uses only interfaces declared by AbstractFactory and AbstractProduct classes.

Collaborations

-

Normally a single instance of a ConcreteFactory class is created at run-time. This concrete factory creates product objects having a particular implementation. To create different product objects, clients should use a different concrete factory.

-

AbstractFactory defers creation of product objects to its ConcreteFactory subclass.

Consequences

The Abstract Factory pattern has the following benefits and liabilities:

-

It isolates concrete classes. The abstract Factory pattern help you control the classes of object than an application creates. Clients manipulate instances through their abstract interfaces.

-

It makes exchanging product families easy. The class of concrete factory appears only once in an application - that is, where it's instantiated. This makes it easy to change the concrete factory an application uses.

-

It promotes consistency among products. When product objects in a family are designed to work together, it is important that an application use objects from only one family at a time. AbstractFactory makes this easy to enforce.

-

Supporting new kind of products is difficult. Extending abstract factories to produce new kinds of Products is not easy. Supporting new kinds of products requires extending the factory interface, which involves changing the AbstractFactory class and all of its subclasses. (Solution in the next section)

Implementation

Here are some useful techniques for implementing the Abstract Factory pattern.

-

Factories as singletons. An application typically needs only one instance of a ConcreteFactory per product family.

-

Creating the products. AbstractFactory only declares an interface for creating products. It's up to ConcreteProduct subclasses to actually create them. The most common way to do this is to define a factory method for each product. A concrete factory will specify its products by overriding the factory method for each. While this implementation is simple, it requires a new concrete factory subclass for each product even if the product families differ only slightly. In many product families are possible, the concrete factory can be implemented using Prototype pattern.

-

Defining extensible factories. AbstractFactory usually defines a different operation for each kind of product it can produce. Adding a new kind of product requires changing the AbstractFactory interface and all the classes that depends on it. A more flexible but less safe design is to add a parameter to operations that create objects. This parameter specifies the kind of object to be created.

An inherent problem remains: All products are returned to the client with the same abstract interface as given by the return type. The client will not be able to differentiate of make safe assumption about the class of a product. The client could perform a downcast, that is not always feasible of safe, because the downcasting can fail.

Sample Code

We will apply the Abstract Factory pattern to creating the mazes.

To better understand the following code and the classes used look here🔗!

Class MazeFactory can create components of mazes. It build rooms, walls, and doors between rooms. For instance, it might be used by a program that builds mazes randomly. Programs that build mazes take a MazeFactory as an argument so that the programmer can specify the classes of rooms, walls, and doors to construct.

public class MazeFactory {

public MazeFactory() {}

public Maze MakeMaze()

{ return new Maze(); }

public Wall MakeWall()

{ return new Wall(); }

public Room MakeRoom(int n)

{ return new Room(n); }

public Door MakeDoor(Room r1, Room r2)

{ return new Door(r1, r2); }

}Here is a version of CreateMaze that take MazeFactory as a parameter. CreateMaze builds a small maze consisting of two rooms with a door between them.

public class MazeGame_Factory {

public Maze CreateMaze(MazeFactory factory) {

Maze aMaze = factory.MakeMaze();

Room r1 = factory.MakeRoom(1);

Room r2 = factory.MakeRoom(2);

Door theDoor = factory.MakeDoor(r1, r2);

r1.SetSide(Direction.North, factory.MakeWall());

r1.SetSide(Direction.East, theDoor);

r1.SetSide(Direction.South, factory.MakeWall());

r1.SetSide(Direction.West, factory.MakeWall());

r2.SetSide(Direction.North, factory.MakeWall());

r2.SetSide(Direction.East, factory.MakeWall());

r2.SetSide(Direction.South, factory.MakeWall());

r2.SetSide(Direction.West, theDoor);

aMaze.AddRoom(r1);

aMaze.AddRoom(r2);

return aMaze;

}

}Now suppose we want to make a maze game in which a room can have a bomb set in it, and if the bomb goes off, it will damage the walls.

We can make a subclass of Room (here 🔗) keep track if a room has a bomb in it.

public class RoomWithABomb extends Room {

int bombDamage;

public RoomWithABomb(int roomNo) {

super(roomNo);

}

public void setBombDamage(int bombDamage) {

this.bombDamage = bombDamage;

}

}We also need a subclass of Wall to keep track of the damage.

public class BombedWall extends Wall {

int wallDamage = 0;

public BombedWall() {

super();

}

public void hitWall(int bombDamage) {

this.wallDamage = bombDamage;

}

}The last class we defined is BombedMazefactory, a subclass of MazeFactory (defined above). This class only need to override two functions:

public class BombedMazeFactory extends MazeFactory {

public Wall MakeWall()

{ return new BombedWall(); }

public Room MakeRoom(int n)

{ return new RoomWithABomb(n); }

}To build a simple maze that can contains bomb or not, we simply call CreateMaze with a BombedMazeFactory or MazeFactory.

public class MainAbstractFactory {

public static void main(String[] args) {

MazeGame_Factory game = new MazeGame_Factory();

MazeFactory factory = new MazeFactory();

BombedMazeFactory bombedFactory = new BombedMazeFactory();

game.CreateMaze(bombedFactory /* factory */);

}

}Notice that the MazeFactory is just a collection of factory methods. This is the most common way to implement the Abstract Factory pattern. Also note that MazeFactory is not an abstract class; it acts as both AbstractFactory and ConcreteFactory.

Known Uses

InterViews uses the "Kit" suffix [Lin92] to denote AbstractFactory classes. It defines WidgetKit and DialogKit abstract factories for generating look-and-feel-specific user interface objects. InterViews also includes a LayoutKit that generates different composition objects depending on the layout desired.

Related Patterns

AbstractFactory classes are often implemented with factory methods, but they can also implemented using Prototype.

A concrete factory is often a singleton.